When is an animal — or even an AI — a person?

Last week, New York state’s highest court ruled that an elephant isn’t a legal person.

The elephant in question is Happy, who’s been kept at the Bronx Zoo for the last 45 years and in isolation for the last 15. The Nonhuman Rights Project, the animal rights nonprofit that brought the case on behalf of Happy, sought to transfer her from the zoo to a roomier elephant sanctuary by invoking habeas corpus — a constitutional right to stop illegal detainment.

To win Happy’s release, Nonhuman Rights Project had to persuade a seven-judge panel in New York that she’s a “legal person,” a term for an entity with rights. No animal in the US has ever been granted legal personhood, so Happy’s case was always a long shot, but other countries have granted aspects of legal personhood to forests and bodies of water, as well as an orangutan. And as Mitt Romney famously told a heckler at the Iowa State Fair in 2011, “corporations are people, my friend.” (Corporations indeed benefit from legal personhood in the US).

Nonhuman Rights Project argued that because elephants suffer in the confinement of zoos and there’s significant evidence that elephants like Happy are autonomous and self-aware, they too should be eligible for release under the “great writ” of habeas corpus. (In 2006, Happy became the first elephant to ever pass the self-recognition mirror test, demonstrating the capacity to distinguish herself from other elephants.)

But writing the court’s majority 5-2 decision, Chief Judge Janet DiFiore argued that granting habeas corpus to a nonhuman animal has never been done in the US and that doing so “would have an enormous destabilizing impact on modern society.”

“The other side has always tried to frighten the courts and make them think that if we won a habeas corpus case on behalf of an elephant, that meant that we would end agriculture … and then we’d start taking your dogs away,” Steven Wise, Nonhuman Rights Project’s founder and president, told me. But Wise says “Habeas corpus focuses on one thing: the single entity who is being imprisoned. In our case that was Happy.”

New rights for new times

To be fair, it’s not hard to imagine that if a judge one day deems an animal a legal person, it’ll open the floodgates with petitions to free other animals. But our lack of legal protections for animals has already had a destabilizing impact on modern society, given that our factory farming of them is a leading cause of climate change, air and water pollution, biodiversity loss, and pandemic risk. We should worry more about the harms of hoarding rights, not expanding them.

However, I do worry a little about what effect granting legal personhood for individual animals would have on society’s views about animal protection. If it happens, it would be a watershed moment for animal law. But only invoking constitutional rights for species “for whom there is robust, abundant scientific evidence of self-awareness and autonomy” like elephants and chimpanzees, as Nonhuman Rights Project’s website states, could also further entrench the commonly-held belief that the more intelligent an animal is, the more worthy they are of protection (a belief that leads to rather dark places when applied to humans).

When I asked Wise about that worry, he said “We’re not arguing for any more [than Happy’s release], we’re not arguing for any less.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23636167/GettyImages_460776070.jpg) Juan Mabromata/AFP via Getty Images

Juan Mabromata/AFP via Getty Images

The Wildlife Conservation Society, which manages the Bronx Zoo, declined to be interviewed for this story, but pointed me to its May 2022 statement issued on the day of oral arguments in the Happy case, which read in part: “[The Nonhuman Rights Project] are not ‘freeing’ Happy as they purport, but arbitrarily demanding that she be uprooted from her home and transferred to another facility where they would prefer to see her live. This demand is based on a philosophy and does not consider her behavior, history, personality, age and special needs.”

Given that animals are primarily property under the law and the kinds of systemic mistreatment that classification permits, Nonhuman Rights Project wasn’t surprised by the outcome of Happy’s case. One line in the decision, one that much of the argument hinged on and has been repeated by other judges, helps explain why: “… the great writ [habeas corpus] protects the right to liberty of humans because they are humans with certain fundamental liberty rights recognized by law.” In other words, Happy can’t be freed from confinement for the basic fact that she is not human.

The idea that a right can only apply to a human simply because they are a human goes by many names: human exceptionalism, anthropocentrism, speciesism. It’s the subtext to our relationship with all other animals: We humans (however unevenly) enjoy certain rights merely because we’re human, while the millions of other species with whom we share the Earth are subject to our whims.

In his dissent, Judge Rowan Wilson called on his colleagues to challenge that exceptionalism: “The majority’s argument— ‘this has never been done before’— is an argument against all progress, one that flies in the face of legal history. Inherently, then, to whom to grant what rights is a normative determination, one that changes (and has changed) over time.” Wilson added, “The correct approach is not to say, ‘this has never been done’ and then quit, but to ask, ‘should this now be done even though it hasn’t before, and why?’”

Five of the seven judges did quit at “this has never been done before,” though two didn’t, and Wise says that’s a major sign of progress unto itself. Nonhuman Rights Project filed its first habeas corpus litigation in 2013, and back then, “I don’t think there was any [judge] who had any agreement with us at all for the first four years,” Wise told me. “And now we’ve had six judges in New York [who’ve] agreed with us.”

They may pick up more support in the coming years: Last month, Nonhuman Rights Project filed a lawsuit on behalf of three elephants in California and has plans to file similar litigation for elephants in a couple of other states, as well as India and Israel.

Sentience beyond the animal kingdom

A few days before Happy lost in court, the status of another nonhuman entity was also called into question. A Google engineer named Blake Lemoine was put on leave for raising alarm bells about his belief that an artificial intelligence (AI) language model that he worked on, called LaMDA, had become sentient.

As my colleague Dylan Matthews wrote, in its exchanges with Lemoine, “LaMDA expresses a deep fear of being turned off by engineers, develops a theory of the difference between ‘emotions’ and ‘feelings’ … and expresses surprisingly eloquently the way it experiences ‘time.’”

The expert consensus is that no, LaMDA is not sentient, even if it’s really good at acting as if it is, though that doesn’t mean we should totally rule out the possibility of AI eventually becoming sentient.

But making that determination would require us to have a deeper understanding of what consciousness really is, notes Jeff Sebo, a philosopher at New York University who studies animals and artificial intelligence.

“The only mind that any of us can directly access is our own and so we have to make inferences about who else can have conscious experiences like ours and what kinds of conscious experiences they might be having,” Sebo told me. “I think the only epistemically responsible attitude is a state of uncertainty about what sorts of systems can realize consciousness and sentience, including certain types of biological and artificial systems.”

While there was an outpouring of sympathy for Happy on social media, there was also plenty of derision — and in the court’s decision — directed toward the idea that an elephant should be deemed a legal person. Lemoine endured even more scorn for claiming that an AI is conscious.

I felt a little of that scorn myself — call it biological exceptionalism. We have such little concern for many of our fellow humans, let alone animals, that fretting over an AI’s feelings seems a bit rich. But while reading the dissenting opinions in the Happy case, I was reminded that I probably shouldn’t hold that view too tightly. The circle of who and what is deserving of moral consideration has continually expanded, and a widely held view today could be a foolish view, or even monstrous one, decades from now.

The day that an elephant is freed from a zoo using a centuries-old human rights law will only help one elephant, but it’ll be a milestone in the fight for expanding humanity’s moral and legal circle, and it might happen much sooner than you think. It might also make concerns for the wellbeing of less cognitively-complex animals, even artificial intelligence, just a little less foreign — and perhaps prepare us for a future where sentience is far more widely recognized than it is today.

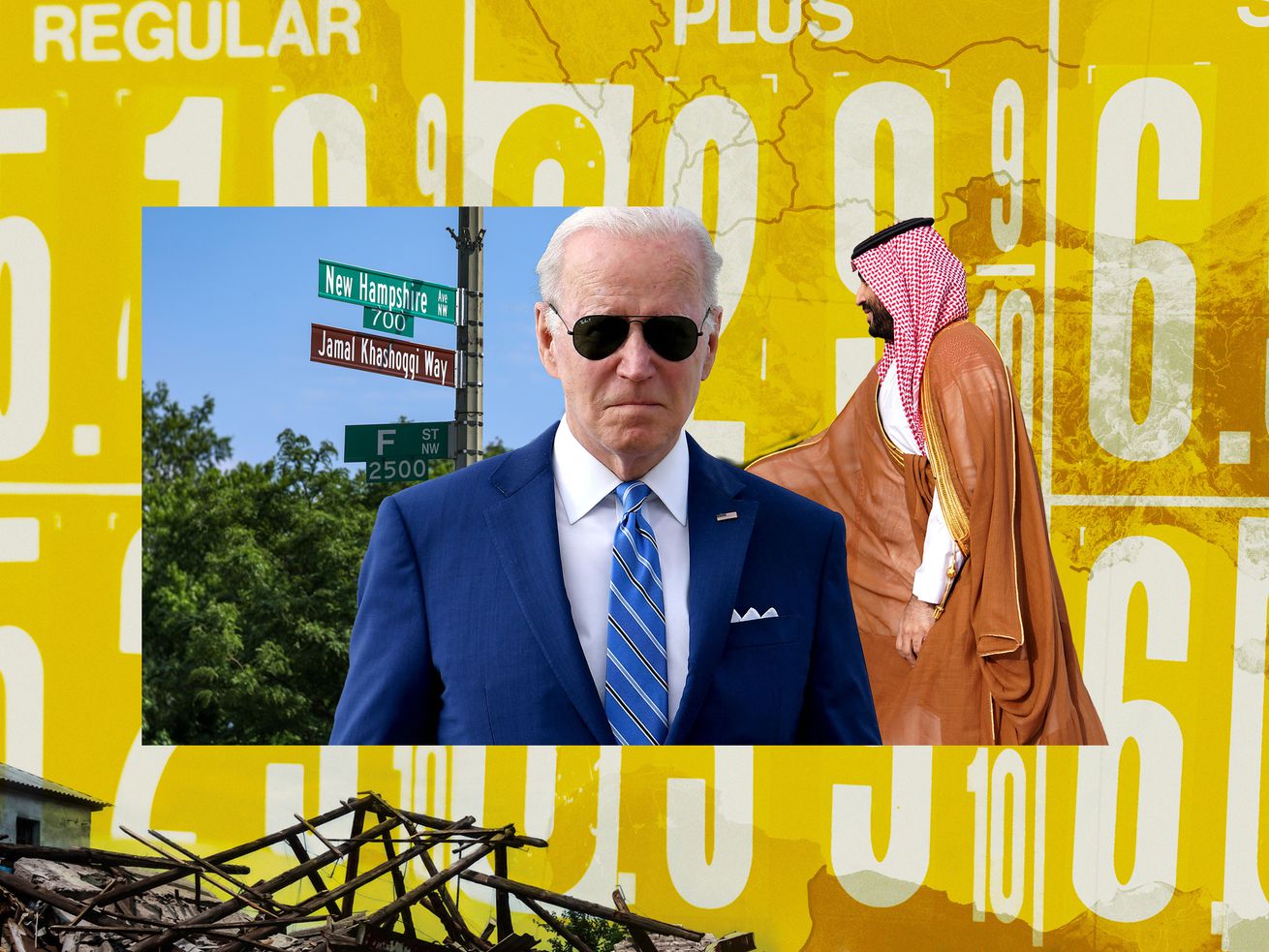

A “foreign policy for the middle class” and centering human rights collide in the Middle East.

As the average national gas price topped $5 a gallon, the White House formally announced that President Joe Biden, in a significant policy turnaround, would be traveling to Saudi Arabia.

On the campaign trail, Biden had called the oil-rich kingdom a “pariah” in response to US intelligence groups’ conclusion that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman bin Abdulaziz ordered the killing of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi. Though the US relationship with Saudi Arabia teetered along in the background, Biden had resisted directly meeting MBS. But July 13-16, he’ll travel to the Middle East. He’ll visit the Saudi city of Jeddah and meet about 10 Arab heads of state and travel to Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory.

Biden’s decision to go to Saudi Arabia in July as part of his first Middle East trip as president reveals the tensions at the heart of his foreign policy.

So far, there have been two foreign policy bumper stickers of his administration. The first: putting human rights at the center of foreign policy. As the US has put its diplomatic power into supporting Ukraine, Biden and his team lately have framed the issue more as supporting democracies versus autocracies.

The second bumper sticker is a foreign policy for the middle class, which feels like the international counterpart to Build Back Better. The idea, which Biden had put forth when campaigning, is that foreign policy is too often divorced from the daily lives of Americans in the heartland, and that what the US does abroad should work for them.

But making the case of a foreign policy for the middle class is tough when Biden’s signature foreign policy initiative — supporting Ukraine in Russia’s war of aggression, partly by levying sanctions on Russia’s energy exports and more — has exacerbated a volatile economic situation for middle- and working-class Americans.

It’s in this Middle East trip that these two taglines collide, as Biden will advocate for the US middle class in Saudi Arabia by focusing on energy policy (and regional security), thereby not centering human rights or democracy. “Look, human rights is always a part of the conversation in our foreign engagements,” a senior administration official said at a recent briefing. That’s a much softer message than putting human rights at the center.

Biden is not the first American president who has struggled to balance competing interests and values in the Middle East, but his two slogans uniquely capture this tension.

The problem is: If Biden’s Saudi Arabia visit might only incrementally lower gas prices, will it benefit the middle class?

The central tension of Biden’s foreign policy

The rollout of the trip has hardly shown any excitement on the president’s part to make amends with MBS. It was reported on June 2, and then the visit was pushed off a month, and only confirmed last week, with officials reluctant to say whether Biden would sit down with MBS (though the Saudi embassy did confirm it). On Friday, Biden said, “I’m not going to meet with MBS. I’m going to an international meeting, and he’s going to be part of it.”

The president’s team has conveyed that human rights remains on the agenda. As White House spokesperson John Kirby said, “I can just tell you that — that his foreign policy is really rooted in values — values like freedom of the press; values like human rights, civil rights.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23636332/GettyImages_1241331215.jpg) Nathan Howard/Getty Images

Nathan Howard/Getty Images

There seem to be conflicting goals among Biden’s slogans and his top hires, and perhaps for Biden himself. The president may be the most resistant to meeting MBS. He said that his presidency “should stand for something,” when privately renouncing a prospective meeting with MBS in recent weeks, according to Politico, in what seemed like an Aaron Sorkin scene.

Biden’s unscripted comments in the past have also given a window into his thinking. At a Harvard Q&A in 2014, he chastised Arab and Muslim countries the US partners with for compounding the civil war in Syria; he blamed Saudi Arabia, among others, for contributing to violent extremism there. “Our biggest problem was our allies,” Biden said. When asked about how human rights considerations affect the US approach to Saudi Arabia, he said, “I could go on and on and on.”

His “pariah” comment and condemnation of Saudi Arabia at Democratic presidential debates also reflected more off-the-cuff remarks.

In short, “centering human rights” seemed to be not just a reaction to President Donald Trump’s coziness with dictators, but also a reflection of Biden’s gut feeling about democracies delivering better for people.

But Biden, on the campaign trail and in office, also talked adamantly about creating a foreign policy for the middle class. To add substance to the slogan, his advisers in 2020 released a think tank report that outlined the economic and trade implications of foreign policy that would “work” for the middle class. Its key recommendations are widely supported, albeit vague, like pursuing trade policies that create jobs, rebuilding relationships with allies, and protecting supply chains and people alike from inevitable economic shifts. There was little discussion of fossil fuel policy, though, except for a call to transition to renewable and green energy sources.

Now, with gas prices as high as they are, contributing to worsening inflation, that blueprint is being put to the test.

Domestically, “Biden’s drilling policies have nothing to do with gas prices,” as Vox’s Rebecca Leber explained. Internationally, the sanctions on Russia, along with surging post-pandemic demand, have contributed to the high price of global crude oil. Since imposing the sanctions, the White House has accelerated its energy diplomacy with countries like Venezuela and others.

The Biden White House is emphasizing the president’s commitment to human rights, while planning a trip to Jeddah with Arab leaders that looks like the opposite of the Summit for Democracy Biden hosted in December.

Some observers, like Khalid Aljabri, a Saudi entrepreneur and physician, think the administration can do both. “Despite being a victim of MBS and my family suffering on a daily basis from his ruthless campaign of intimidation” — Aljabri’s father is a former Saudi intelligence leader whom MBS has targeted, and Aljabri’s siblings are jailed in Saudi Arabia on spurious charges — “I still want to help the US relationship,” he told me. “I don’t think this is a fight of interest versus human rights. I think they’re intertwined.”

This tension is also reflected in the personnel Biden has hired. “Candidate Biden said stuff that he did not even implement in his choice of the people who are going to manage this relationship,” Yasmine Farouk, a researcher at the Carnegie Endowment of International Peace, told me. Most Biden appointees agree that, on Saudi Arabia, “we should preserve this partnership and make it better, instead of having them as enemies or, you know, keeping in distance with them.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23636288/GettyImages_673190748.jpg) Bandar Algaloud/Saudi Kingdom Council/ Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Bandar Algaloud/Saudi Kingdom Council/ Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The White House’s Middle East coordinator Brett McGurk, who has described himself as “a friend of Saudi Arabia,” epitomizes that worldview. “Look, I’ve worked with MBS, and he actually is someone who you can reason with,” McGurk said in 2019, when he was in the private sector. It was almost a year after MBS, the CIA had determined, had ordered the assassination and dismemberment of Khashoggi. In recent months, McGurk and energy envoy Amos Hochstein have been shuttling to Saudi Arabia.

It’s a contrast to other administration officials’ views. USAID Administrator Samantha Power delivered a talk billed as focused on “strengthening democracy and reversing the rise of authoritarianism across the world,” this week. “Look, on the Saudi trip, you know … we have significant concerns about human rights. I think President Biden has been clear about that, will be clear about that,” she said.

Though Biden in his first month did release the US intelligence report showing MBS’s responsibility for the Khashoggi murder and other authoritarian acts, human rights watchdogs say that not enough has been done to hold MBS accountable, like directly sanctioning him. A group of NGOs called on Biden to establish preconditions for the trip, including releasing political prisoners documented by the State Department, ending travel bans and other surveillance tactics, a moratorium on executions, and improving women’s rights.

A former State Department official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said that human rights is just one item on a long list of issues. “I don’t see it being the make or break issue that, frankly, it has never been,” the official said.

Saudi oil isn’t going to make a huge difference for Americans

When the decision to travel to Saudi Arabia was first reported earlier in June, the trip was framed as about finding any way possible to lower oil prices while the US leads a charge against Russia, a major oil producer. But energy experts say that even with Saudi Arabia’s spare capacity and influence among other oil-producing countries in the region, there is no tap that can be quickly turned on.

“If any Americans are paying close attention to this, they couldn’t be faulted for thinking that President Biden is going to go to Saudi Arabia and then the next day, gas prices are going to come down,” Amy Hawthorne, of the Project on Middle East Democracy, said.

But, she and others said, that’s not how oil prices work.

Gas prices are high for two main reasons: issues with refineries’ capacity (which is low) and the price of crude oil (which is high due to demand surging during the relative Covid-19 recovery and supply dropping as less Russian oil enters the market). “The root cause is not about Saudi Arabia,” said Karen Young, an energy expert at the Middle East Institute. “But I think the administration is sort of focused on Saudi Arabia as a lever.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23636307/GettyImages_1237153265.jpg) Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty Images

Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty Images

Saudi Arabia could make a gradual adjustment to the global supply. As a leader within the oil-producing group OPEC+ (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, plus Russia), Saudi Arabia could push to ramp up oil production, but the group’s spare capacity is limited. Young says that Saudi Arabia probably could boost it an additional 2 million barrels a day. “It doesn’t necessarily do much to change where prices are,” she said.

Still, Biden seeks to do everything to lower prices. “It’s clear that this president — like just about every other president out there — wants to be understood by the American public as doing as much as he can to put pump prices in a downward motion,” said Jonathan Elkind, a former senior Obama Energy Department official who’s now at Columbia University.

Oil prices relate to factors that neither the US nor Saudi Arabia has individual control over, Elkind reiterated. But he added that Saudi producing more could make an incremental difference, and “you put enough increments together, and all of a sudden, you’ve got a sizable impact.”

If not oil, what is the purpose of the Mideast trip?

This week, Biden’s team has presented the trip as something different — perhaps more ambitious on Middle East policy and less ambitious on energy.

As the senior official briefed the press on the trip, the list of what would be accomplished got long: “expanding regional, economic, and security cooperation, including new and promising infrastructure and climate initiatives, as well as deterring threats from Iran, advancing human rights, and ensuring global energy and food security.”

The best prospect for success on the trip is in consolidating the Yemen ceasefire that has held for almost three months. US diplomat Tim Lenderking quietly negotiated the deal, after seven years of the Saudi-led coalition bombing the country. The US is in some ways a party to the conflict. The Department of Defense has “administered at least $54.6 billion of military support to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) from fiscal years 2015 through 2021,” according to a newly released Government Accountability Office report. Biden last year said the US would stop supporting “offensive operations” in Yemen, though the suffering from US weapons continues.

Peace in Yemen is critical, but it doesn’t require a presidential visit.

There are a number of other goals the administration might pursue. Going to Saudi Arabia to assuage the concerns of the kingdom and other Arab states about a nuclear agreement with Iran may be a worthwhile endeavor — except that Iran and the countries negotiating with it, including the US, appear far from reviving the deal.

Biden may try to get Arab states more committed to sanctioning Russia; Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and others have been reluctant to pick a side in the conflict. And Israeli security will, at least implicitly, be baked into Biden’s meeting with Arab leaders as his team seeks to build on the Trump administration’s normalization agreements between Israel and Arab states. (The Israel and Palestine stops will have their own issues and pitfalls.)

One possible outcome of the trip would be a move toward rebuilding an institutional relationship with Saudi Arabia.

While the kingdom was conservative in all senses of the word before MBS, it did have a more consultative governing process and less restrictive political environment, and the US maintained normal relations with the royal family’s government. The Biden administration has resisted deepening relations with MBS so far. Biden also didn’t quickly dispatch a US ambassador to Saudi Arabia. The nomination hearing for his choice, Michael Ratney, was held last week, and Biden announced his nomination more than a year after taking office.

Aljabri thinks the White House and National Security Council are playing too big of a role in engaging Saudi Arabia’s leadership and the US government should work more closely with Riyadh through established forums. That would look less like National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan meeting with MBS, or McGurk managing high-level relationships, and more like engagement up and down the Saudi system.

“Trying to rekindle the institution-to-institution partnerships between high-level officials, and taking MBS out of the equation is the way forward,” Aljabri said.

Still, more engagement risks empowering MBS. He is more of a Saddam Hussein-like leader than a benign dictator, critics warn, and he may not be a trustworthy partner.

Bruce Riedel, a former intelligence official who has worked extensively in the Middle East, described MBS as a rogue leader who, in an unprecedented fashion, has jailed members of the royal family to consolidate his power. “The result of this is a recklessness that has been truly astounding,” he told me.

“To me, it’s an unnecessary visit that is not likely to enhance the president’s poll numbers,” said Riedel, who is now a Brookings Institution fellow. “In fact, it’s likely to diminish them, because when you get to the first of August, and the price at the gas station is still $5 a gallon, people are going to be pretty disappointed: ‘So we went to Saudi Arabia, what is the payoff for me?’”

Even a Wall Street-endorsed climate rule is facing serious headwinds.

As drought spreads and sea levels rise, the economic impacts of climate change will run in the trillions of dollars. The insurance firm Swiss Re projects climate disasters would cost the world as much as $23 trillion by 2050, bigger than the impact from the pandemic and the Great Recession of 2009 combined.

It’s reasonable business planning to account for all this foreseeable risk — just like planning for cyberattacks or business disruptions from a pandemic. Last year, for instance, the US had to spend $145 billion dealing with floods, fires, and other climate-related disasters.

Yet somehow, climate change has fallen through the cracks of US financial regulation. Publicly traded companies are required to disclose information about “material” risks that affect their company regardless of their cause, from sanctions to supply chain chaos. But there are no uniform standards for disclosing how much fossil fuel pollution they generate or the impact that climate change could have on their future growth. Instead, companies have been left free to inflate their environmental progress, all with little scrutiny from the public.

This kind of information is, in theory, essential to a functioning free market, so investors can make decisions based on complete information. But fossil fuel interests, conservative ideologues, and corporate trade groups are striving to keep shareholders in the dark on climate risks.

The Biden administration is trying to make companies more publicly accountable for the risk of the climate crisis. A linchpin of Biden’s plan is a draft rule the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed in March. Over 500 pages, the SEC rule proposes that publicly traded companies disclose how climate change affects their business outlook and identify a board member or board committee to focus on climate-related risks.

Once the rule is finalized, companies will have to disclose how their operations are affected by extreme weather events and the impact of climate change on the short- and medium-term business outlook. They’ll also have to report the emissions both from their company’s operations and from how their products are used. This is particularly bad news for fossil fuel companies with business models predicated on selling pollution. Until this rule, they haven’t had to fully account for the environmental impact from things like selling gas that’s burned by consumers’ cars.

“This is a rule, in other words, that helps the free market act like the free market, giving investors exactly the information they need to make the decisions,” Emory University business law expert George Georgiev said.

As the draft rule’s comment period came to a close, it’s clear any regulation on climate change faces serious headwinds. The loudest protests have come from right-wing groups and corporate-aligned nonprofits that have flooded the public comments with previews of the argument they’ll take to courts.

Plenty of businesses in the financial sector stand to benefit from this rule, like the investing giant BlackRock, which has pledged to align its assets with climate goals. But some could be hurt. The companies that benefit from greenwashing their climate commitments are doing everything they can to protect the chaotic status quo.

Financial transparency on climate change is hardly a radical idea

The SEC has required and standardized public company disclosures since 1933. In recent decades, the SEC has issued nonbinding guidance on how publicly traded companies should consider Covid-19 disruptions, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and even a feared “Y2K” meltdown at the turn of the 21st century, so the companies would meet their fiduciary duty.

But the SEC has been painfully slow on climate change. Right now, businesses disclose the risks and costs of their business on the climate on a voluntary, patchy basis with no clear standardization.

A 2020 Government Accountability Office surveyed 32 midsize and large publicly traded companies and found little consistency. Airlines, for example, used years anywhere between 1990 and 2017 as the baseline for calculating their climate footprint. Water companies have used completely different measurements for reporting water extraction. Some companies would just report carbon emissions, while others would report total greenhouse gas emissions (including sources like methane).

The proposed SEC rule cites other evidence of companies not paying attention to this risk, like an internal survey of climate-related keywords in companies’ 10-Ks between June 2019 and December 2020. They found only 31 percent mentioned climate change at all.

This information is not just to benefit climate change efforts; it is also useful to investors. It makes clearer, for instance, that a retail company’s warehouses might be threatened by increased flooding, that an airline company might have to ground more flights because of rising heat waves, or that a bank’s backing of major fossil fuel expansion has the strong chance of backfiring in a world that transitions to renewables. Without any regulation and standardization, companies will just continue to try to outshine one another on their environmental and social commitments without hard data to back it. This mismatch will become an existential risk to financial instability if, for example, extreme weather pummels a business that did not prepare accordingly.

Environmental activists have pushed for more from companies by proposing shareholder resolutions at annual meetings that ask for more transparency, but have met with mixed success in shareholder votes that don’t bind the company to taking action.

In this regulatory vacuum, voluntary global affiliations have cropped up, including the Net Zero Assets Managers Initiative, representing some $43 trillion in assets, and Climate Action 100+, representing more than $60 trillion. Another of these groups is run out of the Financial Stability Board as a Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), a voluntary system that has grown to more than 3,000 companies. The task force’s recommendations tell companies to consider the short-, medium-, and long-term climate impacts, emissions that result from investment decisions, and their operations’ pollution, and account for the changing climate’s consequences for the business. The hundreds of companies that voluntarily comply with these standards aren’t necessarily green or good for the environment, but it’s an extra gold star for their sustainability transparency.

Eight countries, including the UK, have passed laws that will mirror the TFCD’s recommendations, but the US would remain an outlier without the SEC rule. “Investors put their money where they think there’s a good opportunity and good information,” said Seth Rothstein, managing director of the Ceres Accelerator for Sustainable Capital Markets. “If we don’t have good information, we run the risk of falling behind internationally.”

The SEC’s rule is basically the US playing catch-up, based on standards the mainstream corporate community aligned with TFCD have already backed.

Initially, companies will have to spend extra to comply with the rule — up to $530,000 a year for larger companies by the SEC’s estimate, but it will vary depending on how much companies are doing already on climate disclosure. Typically, the costs of rules shrink over time. Otherwise, the rule itself is quite modest. The SEC is “not saying you should or shouldn’t invest in climate products,” said Rothstein. “They’re just saying, tell investors what you’re doing and do it in a consistent way.”

Environmentalists and some Democratic lawmakers argue the SEC could be doing even more. The SEC does not change how companies disclose climate-related activities like PR campaigns and political influence, the kind of activities that tend to be outsourced to nonprofits that shield their activities from the public. In March, Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) called it a “failure of nerve that shies away from a perfectly legal, necessary response to the climate danger we face” because political efforts remain “the single most material disclosures a company could make to achieve climate safety.”

Right-wing groups claim financial transparency is an attack on free speech

Unsurprisingly, the SEC is facing immense pressure to withdraw this rule because of the same shadowy political spending that companies don’t have to disclose in the first place. Groups like the US Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers, Americans for Prosperity, and the Competitive Enterprise Institute have flooded the SEC with comments that argue company free speech would be violated.

Trade groups and right-wing think tanks have argued that requiring companies to report these emissions is akin to violating their First Amendment rights of free speech, pointing to a court case that ruled a regulation requiring the disclosure of conflict-zone minerals would amount to “compelled speech” and violated the companies’ rights.

The American Petroleum Institute, the oil industry lobby, has argued the rule “could raise serious First Amendment issues under recent applying strict scrutiny to content-based laws compelling speech.”

The argument has found purchase with conservative lawmakers, like West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey, who picked up the argument in his 2021 letter to Treasury last year. In Congress, 19 Republican senators argued in their submitted comments that the rule is “not within the SEC’s mission to protect investors, maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets, and facilitate capital formation.” Another 40 Republican representatives wrote that the rule will act to “undermine and shame public companies,” while Republican attorneys general describes the rule as a “total reordering of [the SEC’s] present disclosure regime.”

The attack on regulation under the guise of First Amendment rights has become more familiar in recent years. “Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has been steadily giving corporations more and more leeway, more and more rights,” said Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, a corporate law expert who has published several books on corporate speech.

The court also opened the door to more of these lawsuits, striking down a California law that required nonprofits to disclose their donors, siding with the Americans for Prosperity Foundation’s argument against disclosing their donors and providing IRS 990 forms to the state. Other legal challenges to campaign finance laws and unions have used the First Amendment.

Legal experts supportive of the SEC rule consider the argument a long shot in courts. “I think that argument is really far-fetched,” Emory’s Georgiev said.

But it’s still worrisome. If it succeeds, whether in courts or as a scare tactic to get the SEC to backtrack, it sets a dangerous precedent for the financial system at large. “If this climate rule is violating the First Amendment, it’s been all nine decades [the SEC has been] violating the First Amendment,” Georgiev said. “They will definitely try it out in courts. At the end of the day, a lot of far-fetched arguments succeed in courts.”